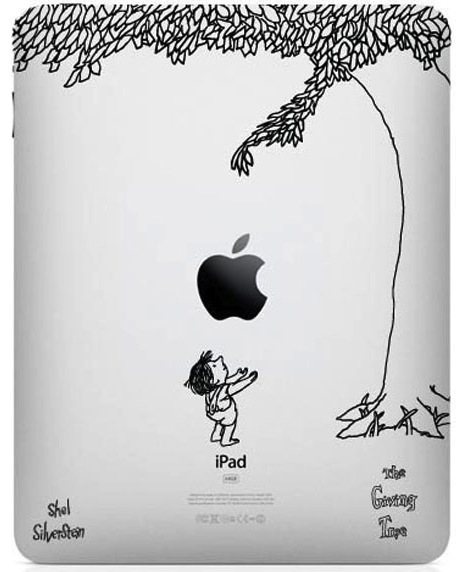

THE GIVING TREE: A Picture Book Without a Hero

/Few picture books seem to be so divisive as Shel Silverstein's The Giving Tree. [1. The movie Blue Valentine contains a charmingly direct critique of the book, which you can read about here. Also a nice article on Silverstein's unlikely rise to kidlit stardom here.] While the book has no shortage of fans, many other people protest how the story sentimentalizes (and promotes) a one-way relationship in which a Tree gives and gives and gives without ever getting so much as a “thank you” from the capricious, selfish boy.

This criticism puts me in a mind of one other great doormat in literary history: William Dobbin from Thackeray’s Vanity Fair.[2. Mary and I have long hoped to one day name a dog “Dobbin” … it is a good name for a loyal friend. (Also, for the curious, the title of this post is a reference to Vanity Fair’s subtitle: “A Novel Without a Hero”.] In a nutshell, Dobbin is a sweet, loyal soldier in love with the vapid-but-beautiful Amelia Sedley. Dobbin spends much of the book as Amelia’s friend, caretaker, and confidant -- putting up with an endless stream of abuse in the process. At first a reader admires Dobbin’s loyalty and firm character, but slowly we start to get the feeling that we are not watching a hero, but a chump.

One of the most shocking (and delightful!) moments in the book comes late when Amelia -- who has since fallen on hard times -- finally condescends to accept Dobbin’s oft-repeated proposal of marriage. And that’s when something wonderful happens: Dobbin rejects her! He finally shows some self-respect and demands a woman who actually appreciates him for who he is. Awesome.

Unlike Vanity Fair, The Giving Tree does not have this satisfying reversal -- at no point does the Tree stand up for herself. Instead she continues to be exploited and (the narrator would have us believe) continues to be “happy”.

What could Shel Silverstein have been thinking?

I’ve recently been spending a bit of time with the book, and I think I’ve found some things in the text that actually complicate the offensive “doormat reading”. Let’s dive in …

2) WHAT KIND OF LOVE? An essential assumption of the doormat-reading is that the book's relationship is meant to be an allegory for romantic love.[4. This is a moment where CS Lewis' exploration of The Four Loves becomes very helpful in articulating such differences. I would argue that Giving Tree haters assume it is a story of "eros" love, whereas defenders see the book as a portrait of "agape" love -- the love that transpires between God and mankind.] However, there are clues in the book that indicate that the dynamic is much closer to parent/child than girl/boy. Consider the fact that the boy moves from child to old man, while the tree essentially stays in a fixed state, always older and wiser. Consider the fact that the Tree shows no jealousy or feelings of betrayal when the boy courts a girl under her eaves. Consider the fact that at every stage, the boy comes to the tree as a provider, rather than a romantic companion. I don’t know why, exactly, but I am much more comfortable with the doormat reading when it is taken out of a romantic setting. No matter what happens, the parent in a parent-child relationship always maintains a degree of dignity and power.

1) "BUT NOT REALLY" Every scene in The Giving Tree ends with a refrain: "And the Tree was happy." Some readers see this phrase as a tacit endorsement of the relationship -- and the boy’s terrible behavior. This, however, assumes that the author is being completely straightforward with the word “happy.” Wouldn’t it be nice if Shel Silverstein found a way to indicate that the refrain “And the Tree was happy” was, in fact, ironic? Lucky for us, he does just that! Right before the final scene, Silverstein adds a twist: “And the Tree was happy … but not really.” Of course this does not instantly negate all of the Tree’s aforementioned happiness, but it does point to the fact that the author understands the difference between declaring oneself happy and actually being happy.

3) "I AM VERY TIRED" I have long maintained that an author cannot hide from his ending: the final scene of every story works as a key with which the reader can unlock and interpret every scene before it. Throughout much of The Giving Tree, it does indeed seem as though Silverstein is sentimentalizing a doormat relationship. The end, however, tells a different story. In the final scene the boy returns to the Tree one last time, now old and decrepit. He is made to remember all the things that he has taken from the tree, each one more humiliating than the last ("My teeth are too weak for apples," "I am too tired to climb," etc.). While he does not openly apologize for his past behavior, I do think that some sense of remorse is implicit in his tone.[4. You will notice that this is the only scene in the book in which he does not directly ask for anything from the tree. Perhaps because he is too ashamed?]

* * *

I suspect the one thing missing for people are the actual words "I'm sorry." The old man may be sad and humiliated, but he is not repentant in a way that we wish he were. To this I would answer that an overt apology would undermine the entire book. The point of unconditional love is that it has no conditions.

Of course, we will never know what Uncle Shelby meant to say in his book. However, I tend to believe that if there are two valid readings of a text -- one of which makes the book awful, and the other makes it better -- we would be best served to grab hold of the reading that lets us enjoy the book. Call it an Occam's Razor of Interpretation.