Risks and Rewards of UN CON VEN SHUN

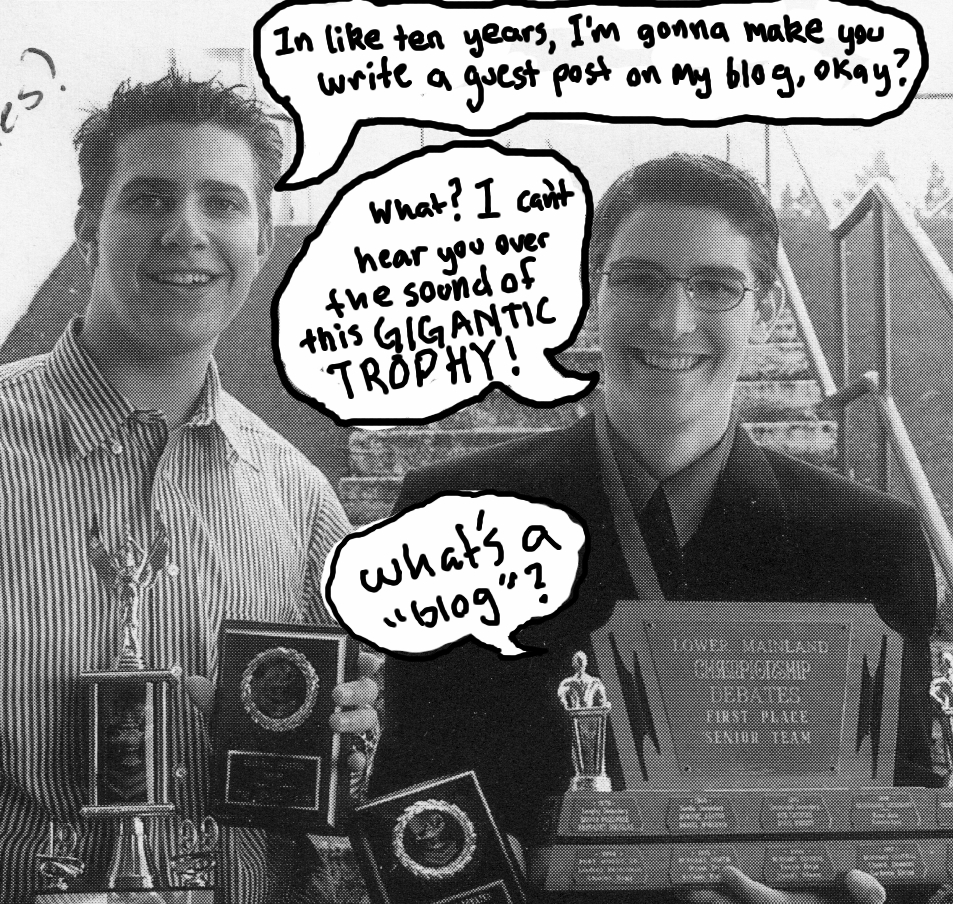

/Today we've got a post from friend and booklover Craig Chapman. Readers of The Scop might recognize his name from the comments section. Back in high school, Craig and I regularly cleaned up in the local debate scene. Look! Here we are in our school year book:

Nowadays, Craig is some kind of mad scientist, but in his spare time he reads a lot of YA. Recently, he was talking to me about China Mieville's YA fantasy, Un Lun Dun. I only know Mieville as the guy who hates Tolkien, but apparently his book made some waves as a sort of anti-Harry Potter. I asked Craig to share some of his thoughts on the blog, and boy did he deliver! Please forgive his ridiculous Canadian spellings ...

Nowadays, Craig is some kind of mad scientist, but in his spare time he reads a lot of YA. Recently, he was talking to me about China Mieville's YA fantasy, Un Lun Dun. I only know Mieville as the guy who hates Tolkien, but apparently his book made some waves as a sort of anti-Harry Potter. I asked Craig to share some of his thoughts on the blog, and boy did he deliver! Please forgive his ridiculous Canadian spellings ...

* * *

Conventions can be liberating. They establish expectations that convey volumes of information. Taking an example from my world of research in behavioural neuroscience, humans have the unique ability to accurately guess what another person is thinking. This ability – referred to as Theory of Mind – is thought to be the base capacity required for successful communication. Here’s an example: You are walking by the office of a co-worker and see that they are looking frustrated while rummaging through an open drawer. You infer that this person is looking for something. Of course, it is possible -- though unlikely -- that they are trying some new exercise regimen. How do you know that the first option, if not correct, is much more likely? The simple answer is that it fits with the context. That is, given the surroundings, your experience with this person, their expression, and even thinking how you might act in the same situation, you expect that they are looking for something. And so you ask “What are you looking for?” instead of “How many calories have you burned”?

Along the same lines, authors can use conventions to convey information without the need to write anything down. Consider a recent post and comments on this blog regarding the ‘Childlit mentor’. It went without saying that we all knew exactly what a mentor was like. They are old, and wise. They help the protagonist when all seems lost, or when things just don’t make sense. By using a convention like the mentor, the author gets all of this content for free. I don’t think I’d even ‘met’ Dumbledore as a reader and I already knew that he was the key to a lot of the challenges Harry would face (and that he was probably an awesome wizard, too!).

Of course, the problem of relying on conventions is that they can become stale – the text that overuses them can feel derivative and ultimately boring.[1. One personal pet peeve is how unimaginative fantasy authors are when conceptualizing how magic might work. Almost always magic is simply the act of thinking really hard, then saying a word (the ‘Force’, the ‘Will and the Word’, ‘Avada Kedavra’ etc.).] Of course an author can decorate convention, dress it up so it seems new or interesting to explore because of its dressing. For the perfect example, you need look no further than Harry Potter. Rowling relies heavily on convention, but gives such exquisite details that it becomes a joy to read what could otherwise have come off as “more of the same.” Still, there is a reason why not everyone is a Rowling: making old conventions novel is ultimately very difficult.

Given the risks associated with over-used tropes, why don’t we read more books that are completely unconventional? The problem is this: if you create something truly new you have to spend a significant amount of text describing how this new thing works. And in doing so you risk losing your reader. Moreover, when a reader fills in the blanks of a story employing a particular convention, they will likely fill those blanks with material that they like. While we might all know what a mentor is, your mentor and my mentor might be different – but as long as the author leaves it to the reader to fill in the details, then each of us can use whatever mentor we like best.

Perhaps there is therefore good reason why we don’t see many examples of true unconvention – because largely it doesn’t work, at least not for a broad readership. But occasionally, I have seen excellent examples of authors being unconventional. In his book Un Lun Dun, China Mieville employs the tactic of anti-convention.[2. Mieville also writes some of the best adult sci-fi/fantasy I have ever read; his book Perdido Street Station is so incredibly imaginative and horrific that it literally gave me nightmares, and his book The Scar (my personal favorite) has the single most memorable image I've ever seen, heard, or read in any medium.] He doesn’t create something new, but rather he uses the exact opposite of a whole host of conventions:

Perhaps there is therefore good reason why we don’t see many examples of true unconvention – because largely it doesn’t work, at least not for a broad readership. But occasionally, I have seen excellent examples of authors being unconventional. In his book Un Lun Dun, China Mieville employs the tactic of anti-convention.[2. Mieville also writes some of the best adult sci-fi/fantasy I have ever read; his book Perdido Street Station is so incredibly imaginative and horrific that it literally gave me nightmares, and his book The Scar (my personal favorite) has the single most memorable image I've ever seen, heard, or read in any medium.] He doesn’t create something new, but rather he uses the exact opposite of a whole host of conventions:

START SPOILER ALERT!

In the book, the Chosen-One is a beautiful blond girl who shoulders her fate with quiet resolve -- but she goes down early and it’s her tag-along, rather-plain friend Deeba who becomes the hero of the story. The prophecy describing how to defeat the evil Smog is spoken by a book, guarded by a sect of wise “Propheseers” -- all of which turn out to be hopelessly false ... not malicious, just wrong. Deeba’s sidekick is a milk carton named Curdle who in the final fight cowers in the corner and at no point does anything to save the hero. And, my personal favourite, when Deeba is faced with completing seven tasks to find seven essential tokens, she decides there is no time and completes the seventh task first, thus acquiring the most essential item (the UnGun, which, as you might guess, works best when firing nothing).

END SPOILER ALERT.

It ends up being a fun exercise to consider all the ways Mieville plays with anti-convention from the title through to the end of the book. It’s almost as much fun to consider whether all of the unconventions are meant to specifically mirror Harry Potter or not.

By using anti-convention, Mieveille still gets all the free content that comes with the expectations associated with conventions. Then, by turning a convention on its head, he makes the unconvention new and interesting for the reader. Ultimately, Mieville is playing a complex game using Theory of Mind. He supposes that his reader will have a whole host of beliefs and expectations that come from the conventions he employs. But more than that, he wagers that he can guess almost the exact content of your beliefs and then invert them; the result runs so counter to what you expected that it is enjoyable.

By using anti-convention, Mieveille still gets all the free content that comes with the expectations associated with conventions. Then, by turning a convention on its head, he makes the unconvention new and interesting for the reader. Ultimately, Mieville is playing a complex game using Theory of Mind. He supposes that his reader will have a whole host of beliefs and expectations that come from the conventions he employs. But more than that, he wagers that he can guess almost the exact content of your beliefs and then invert them; the result runs so counter to what you expected that it is enjoyable.

It’s as though he’s guessing that when I’m reaching in my drawer I’m looking for something, then deliberately asks me how many calories I’ve burned, knowing that I’ll get the joke.