As promised, I'm devoting this entire week to J.M. Barrie's Peter Pan. Today I'd like to discuss the long path leading up to the creation of this iconic character.

Thanks to Johnny Depp, most people know that Peter Pan was a 1904 stage play before it was a novel, but what Finding Neverland fails to mention is that the character of Peter Pan actually goes back even further -- to a book called The Little White Bird. Published in 1902, The Little White Bird was an adult novel that featured an unaging boy named Peter Pan who lived among birds in the middle of Kensington Gardens.

As promised, I'm devoting this entire week to J.M. Barrie's Peter Pan. Today I'd like to discuss the long path leading up to the creation of this iconic character.

Thanks to Johnny Depp, most people know that Peter Pan was a 1904 stage play before it was a novel, but what Finding Neverland fails to mention is that the character of Peter Pan actually goes back even further -- to a book called The Little White Bird. Published in 1902, The Little White Bird was an adult novel that featured an unaging boy named Peter Pan who lived among birds in the middle of Kensington Gardens.

It would be a stretch to call this earlier book a prequel. Yes, the kid's name is Peter Pan, and, yes, he refuses to grow up, but that's where the similarities end. This proto-Peter lacks the cockiness and capricious violence of his later incarnation. When he meets a girl, he asks to marry her. When he's granted a wish by the fairy queen, he asks to return to his mother. I simply cannot accept that this pansy would turn into the pirate-murdering, rooster-crowing, teeth-gnashing Peter Pan that I know and love.[1. there is a whole separate conversation to be had about how the "rules" of Kensington Gardens" don't work with the "rules" of Neverland -- more evidence that the two books were not meant to exist in the same universe.]

I don't think Barrie intended for his readers to see the characters as contiguous. Rather, I think he considered Kensington Peter to be a sort of "dress rehearsal" -- one of many incarnations necessary for the creation of his final character. Even the stage play, which much more closely resembles the 1911 novel, lacks much of the depth of character and theme found in the later book. Scholar Jack Zipes agrees in his introduction to a Penguin edition of Peter Pan:

"There is a sense that [Barrie] wanted to provide definitive closure to the story with the publication of the prose novel in 1911 ... The 'definitive' novel is the most complicated and sophisticated of all the versions of Peter Pan."

As someone who has read Peter Pan a number of times, I think the work shows. The 1911 edition, while simple in language, is unbelievably rich in theme.[2. My wife has observed that she can't read the book with a pen in her hand because she'll compulsively underline every sentence -- they're all that good.] The idea that something this good can only be got after countless revisions thrills me as a reader, but the writer in me trembles. There is something terrifying in the possibility that a great character may take several passes to get right -- that long after publication a story might still bear revision. When do you stop revisiting past work? Unless you're George Lucas, the answer to this question might be "never."

Other Examples of Literary Dress Rehearsals

In the interest of expanding the conversation, I tried to think of some other books that functioned as literary dress rehearsals. I'm sure there are a lot more out there, but here's what came to mind:

Huckleberry Finn - More than once during the latest Huck Finn Debacle, I had to remind myself that Huck started out in 1876 as a supporting character in Tom Sawyer. It wasn't until eight years later that he got his due in Huck Finn.

Huckleberry Finn - More than once during the latest Huck Finn Debacle, I had to remind myself that Huck started out in 1876 as a supporting character in Tom Sawyer. It wasn't until eight years later that he got his due in Huck Finn.

Sara Crewe - Frances Hodgson Burnett's wonderful heroine first found life in a stripped-down serial novel in 1888. Fourteen years later, she appeared in a stage adaptation titled A Little Un-Fairy Princess. It was only after that that Burnett revised A Little Princess to create the Sara we know today.

Sara Crewe - Frances Hodgson Burnett's wonderful heroine first found life in a stripped-down serial novel in 1888. Fourteen years later, she appeared in a stage adaptation titled A Little Un-Fairy Princess. It was only after that that Burnett revised A Little Princess to create the Sara we know today.

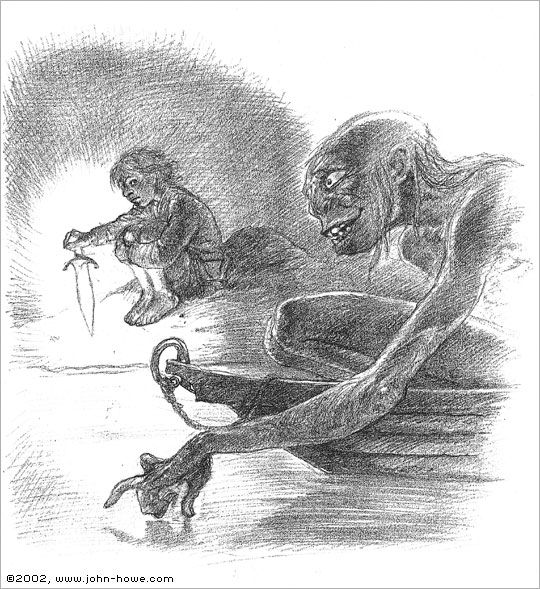

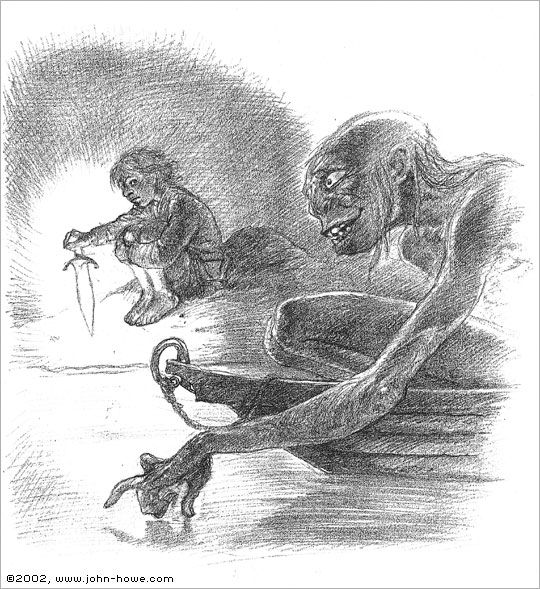

Gollum - In many ways, The Hobbit is a functional prequel to The Lord of the Rings. However, I've always felt there was a serious disconnect in the two characterizations of Gollum.[3. This is closely related to the differing characterization of "the ring," which too conveniently transforms from a straightforward invisibility-device to an all-powerful MacGuffin .] His moral journey in the later books belies the riddle-asking monster-in-the-dark characterization from the earlier volume.

Gollum - In many ways, The Hobbit is a functional prequel to The Lord of the Rings. However, I've always felt there was a serious disconnect in the two characterizations of Gollum.[3. This is closely related to the differing characterization of "the ring," which too conveniently transforms from a straightforward invisibility-device to an all-powerful MacGuffin .] His moral journey in the later books belies the riddle-asking monster-in-the-dark characterization from the earlier volume.

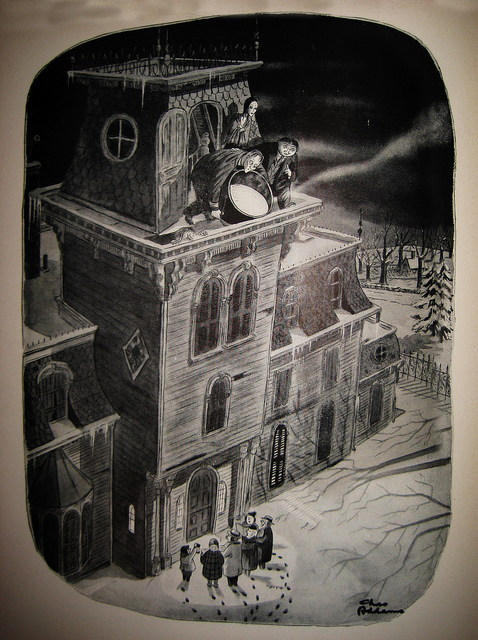

The Addams Family - Strictly speaking, these aren't "literary" characters, but I often think about the fact that Charles Addams drew the members of his "Addams Family" for years before thinking to give them names. It wasn't until the 1964 television show that the family really hit pop culture. Looking back on Addams' older cartoons, you can see how over time he was able to tweak and refine his family into the distinct characters we know today.

The Addams Family - Strictly speaking, these aren't "literary" characters, but I often think about the fact that Charles Addams drew the members of his "Addams Family" for years before thinking to give them names. It wasn't until the 1964 television show that the family really hit pop culture. Looking back on Addams' older cartoons, you can see how over time he was able to tweak and refine his family into the distinct characters we know today.

Bod Owens - A more contemporary example of character dress-rehearsal might be Neil Gaiman's The Graveyard Book. I know a central chapter from the novel ("The Witch's Headstone") was first published as a standalone short story, but I have not read the original version. I'm curious to know whether the characterization of Bod Owens changed in any significant ways -- anyone out there have a copy?

So those are a few literary dress rehearsals that I can think of. I have this nagging feeling that I'm missing some big examples ... feel free to toss in others in the comments.

Tomorrow, check in to learn why I long believed Peter Pan to be an unfilmable story . . . and read about the London stage production that proved me wrong.

* * *

For those who missed the other "Peter Pan Week" posts:

Day Two: The Problem with Peter

Day Three: Tink or Belle?

Day Four: The Neverland Connundrum

Day Five: Loss and Exclusion in Peter Pan (special guest post!)

Also, you can also read my ham-fisted attempt to connect Peter Pan to The Hunger Games here.

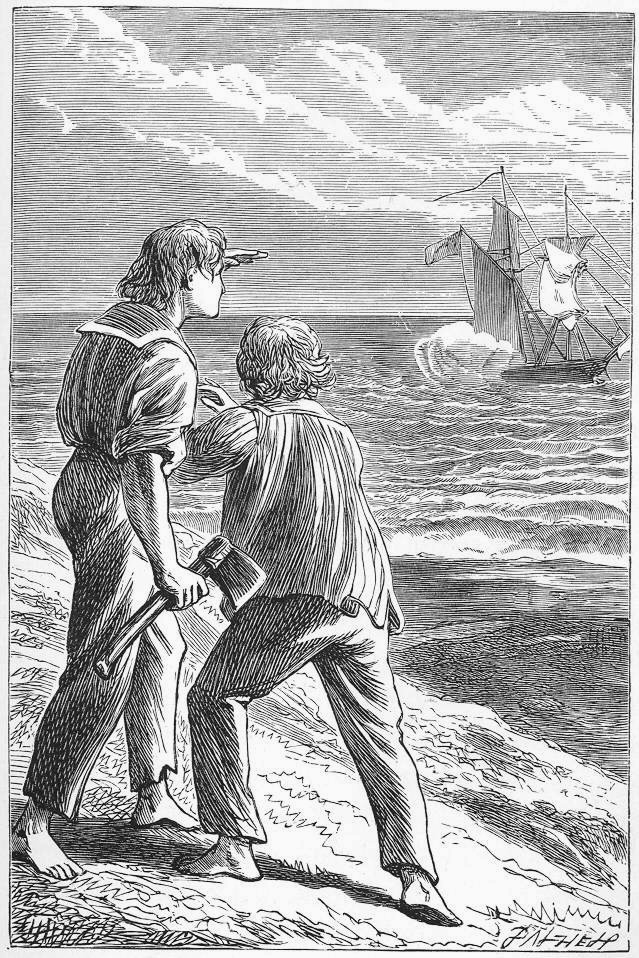

This last week for my Children's Literature course, we read Treasure Island. This is a book I have loved for a long time -- the character of Old Pew was a major influence on Peter Nimble.

Recently, I had students watch a lecture by Mike Hill about the subtextual themes of Jurassic Park. Hill does a great job explaining how great stories contain a primal/Jungian undercurrent that runs beneath the surface plot -- in the case of JP it was about the anxiety of creating a family.

This last week for my Children's Literature course, we read Treasure Island. This is a book I have loved for a long time -- the character of Old Pew was a major influence on Peter Nimble.

Recently, I had students watch a lecture by Mike Hill about the subtextual themes of Jurassic Park. Hill does a great job explaining how great stories contain a primal/Jungian undercurrent that runs beneath the surface plot -- in the case of JP it was about the anxiety of creating a family. ning test of Jim's character -- a moment where he places the integrity of his word as an English Gentleman over even his life.

ning test of Jim's character -- a moment where he places the integrity of his word as an English Gentleman over even his life.

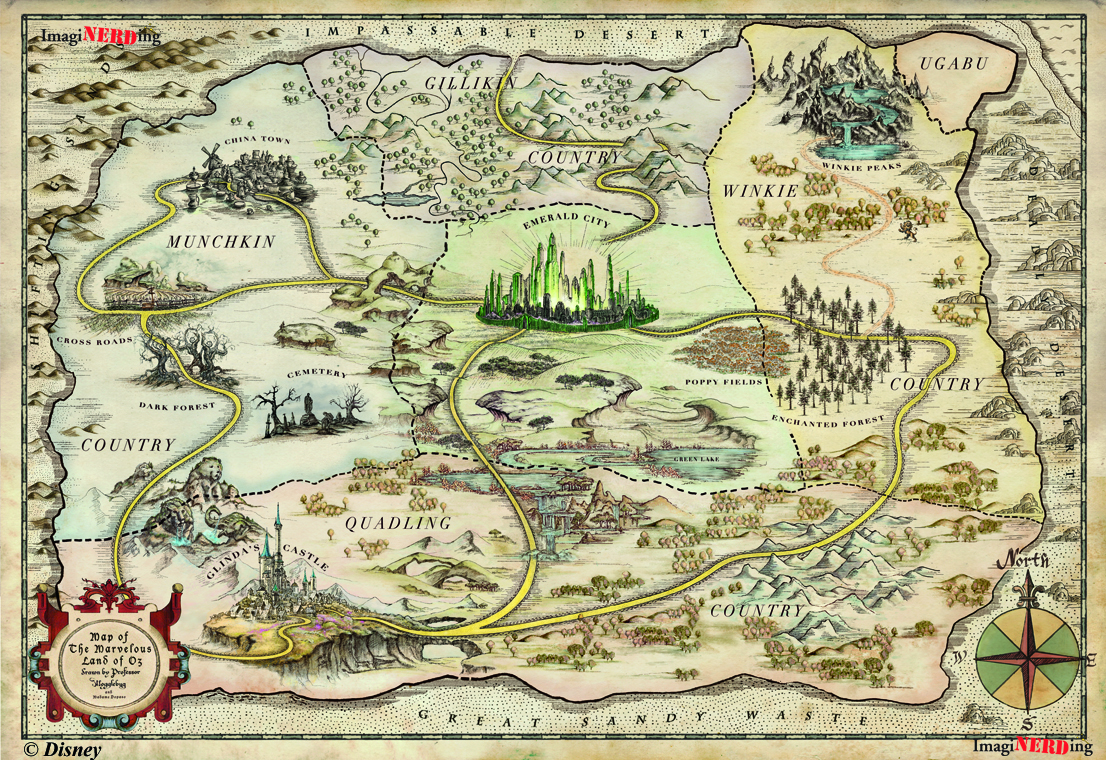

When I teach my Children's Literature course, I always start with a lecture on the "Golden Age" of children's literature--starting with Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and ending (to my thinking) with Peter & Wendy. I wrap up the lecture by identifying six Golden Age children's authors who set the template for what the genre would become in the century to follow. On the list is L Frank Baum, who I credit with creating something that has perhaps had the greatest impact on contemporary storytelling: platform worldbuilding.

When I teach my Children's Literature course, I always start with a lecture on the "Golden Age" of children's literature--starting with Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and ending (to my thinking) with Peter & Wendy. I wrap up the lecture by identifying six Golden Age children's authors who set the template for what the genre would become in the century to follow. On the list is L Frank Baum, who I credit with creating something that has perhaps had the greatest impact on contemporary storytelling: platform worldbuilding. Storytelling utilizes three main tools: character, setting, and action. At various points in history, popular stories have emphasized one or another of these elements. Presently, we are entering an age that celebrates setting above all. Today we value not just compelling narratives (Shakespeare) or characters (Dickens), but settings rich enough to contain a multitude of characters and plots. Think of visionaries like

Storytelling utilizes three main tools: character, setting, and action. At various points in history, popular stories have emphasized one or another of these elements. Presently, we are entering an age that celebrates setting above all. Today we value not just compelling narratives (Shakespeare) or characters (Dickens), but settings rich enough to contain a multitude of characters and plots. Think of visionaries like  Every fall I teach a class at

Every fall I teach a class at

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L Frank Baum (1900)

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L Frank Baum (1900) The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett (1911)

The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett (1911) The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain (1885)

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain (1885) Peter and Wendy by JM Barrie (1911)

Peter and Wendy by JM Barrie (1911) Charlotte's Web by EB White (1952)

Charlotte's Web by EB White (1952)

As promised

As promised